Starting in March of 2020, when COVID-19 officially became everyone’s problem, vaccination was touted as the way out of the pandemic; the light at the end of the tunnel. Development proceeded at breakneck speed, resulting in the availability of not just one but several vaccines by the end of the year. Mass production and distribution took a few months longer, and I got my second shot of Moderna at the end of June. (It is strange that everyone knows, and has opinions about, the specific brand of vaccine they got. I bet that, for any previous shot you’ve had, you never even thought about it).

So, now we’re all vaccinated. … You’ve been vaccinated, right? If not, get vaccinated!

Between “breakthrough” infections (i.e., infections of people who are vaccinated) and new variants of SARS-CoV-2, just how much safer are we than we were last spring? Some reportage annoyingly gives the raw case counts for vaccinated and unvaccinated — annoying because this gives an imperfect, possibly downright misleading picture of how well the vaccines are working. Consider the hypothetical case where 100% of a population have been vaccinated: In that case, all infections will be breakthrough infections, and a vaccine skeptic might claim that this proves the vaccine doesn’t work!

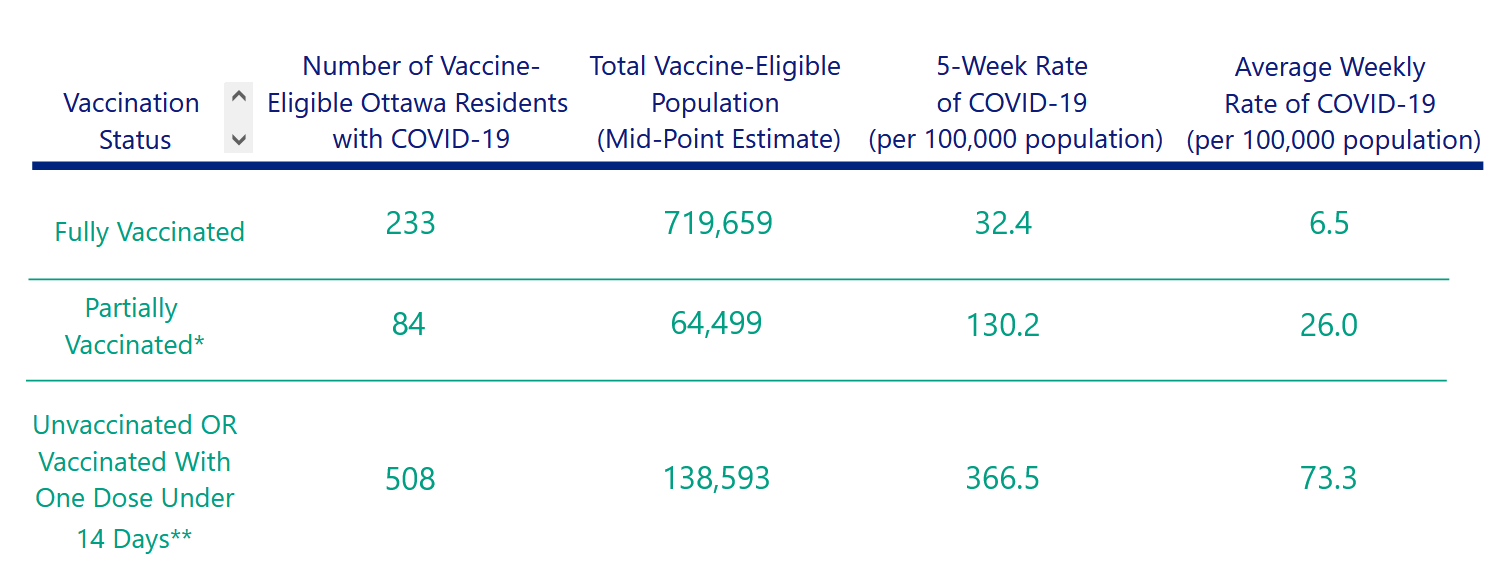

The proper way to calculate the effectiveness of a medical intervention is to normalize the numbers by the sizes of the populations being considered. Consider, for example, the numbers from Ottawa (where I live), covering the period of August 7 through September 10.

Dividing the number of cases (233) among fully vaccinated residents by the total number of vaccinated residents (719,659) yields a rate of 32.4 per 100,000. Doing the same calculation for unvaccinated people yields a rate of 366.5 per 100,000 — over 11 times higher! The same calculation can be done to compare the rates of different disease outcomes against the vaccination status.

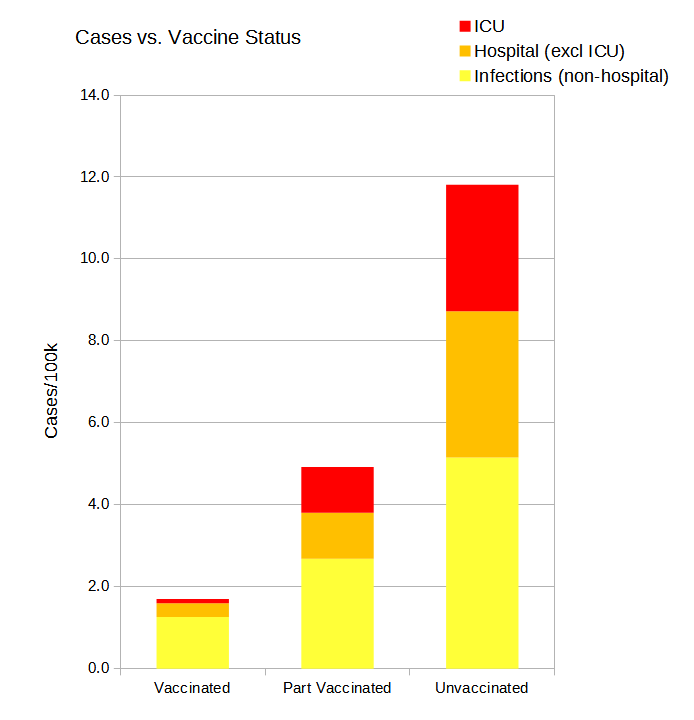

Below is a snapshot of the situation in Ontario on September 19.

Each bar represents the number of cases per 100,000 individuals with that vaccination status, subdivided by severity. Note how much shorter the Vaccinated bar is than the Unvaccinated. But also note how the orange and red areas (hospitalization and ICU admission) are proportionally even smaller. That is how good a job the vaccines are doing of protecting against severe disease. (Did I mention that you should get vaccinated, if you aren’t yet? Get vaccinated.)

Each bar represents the number of cases per 100,000 individuals with that vaccination status, subdivided by severity. Note how much shorter the Vaccinated bar is than the Unvaccinated. But also note how the orange and red areas (hospitalization and ICU admission) are proportionally even smaller. That is how good a job the vaccines are doing of protecting against severe disease. (Did I mention that you should get vaccinated, if you aren’t yet? Get vaccinated.)

What are the risks? Nothing is ever completely safe, and humans are notoriously bad at assessing relative risks, and responding appropriately. We tend to overreact to small but frightening risks, while leaving ourselves vulnerable to much larger hazards.

I suggest that the rational response here is first to define what one would consider an unacceptable outcome; and second, to behave so as to reduce one’s risk of that outcome to the magnitude of other risks we routinely accept without worrying too much about them. Obviously, I consider death or a life-changing outcome (e.g., long covid) to be unacceptable, and am also strongly averse to contracting any infection at all, because of the hazard it would pose to other family members.

Now, what other hazards do I face? Consulting Statistics Canada mortality tables, I find that a man of my age (64) in Ontario has a roughly 1 to 1.5 percent chance of dying of all causes within a year. (My personal prospects are probably a bit better than that, since that figure includes individuals already diagnosed with conditions such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, etc.).

What else? According to the National Cancer Institute, the annual chance of being diagnosed with cancer for a man my age is also about one percent or so. I try to lead a healthy lifestyle, but I don’t lose sleep over it, so it seems I am comfortable with about a one percent chance per year of some serious adverse health event.

With that in mind, just what is safe (i.e., within my one percent comfort margin) for me to do? I don’t want to go out and party like it’s 2019 if it will make me sick, but I also don’t want to cower in my basement if it means I am foregoing activities which would be both safe and enjoyable. The risk of infection depends on a number of factors: the number of people you are in contact with; the probability that one or more of them are contagious (depends on the case rate in your area); how closely, for how long, under what conditions of ventilation (e.g. indoor vs. outdoor) was the contact; and of course whether individuals are vaccinated, wearing masks, and talking vs. shouting vs. singing.

It all seems a bit complicated, doesn’t it?

Fortunately a group of dedicated geeks have sweated the literature, cranked the numbers, and shared the results of their labours with the world: The microCOVID Project provides a webpage that allows you to estimate your risk of being infected with SARS-CoV-2 for any given activity. The page quantifies risk in “microCOVIDs,” each representing a one-in-a-million chance of becoming infected. Thus, allowing a one-percent-per-year risk gives me a “risk budget” of approximately 200 microCOVIDs per week. (The page allows you to set your acceptable risk level higher or lower.) I can do anything I like, as long as the total risk does not add up to more than 200 microCOVIDs in any given week.

For example, suppose I am invited to a three-hour backyard barbecue in Ottawa (the page accesses public health data for specific locations), with a dozen people, all of whom are vaccinated, and none of whom will be wearing masks. When I set all those values on the microCOVID page, it informs me that the barbecue presents a risk of 20 microCOVIDs, or one-tenth of my weekly risk budget. This includes an uncertainty range estimate of three. Note that toggling the vaccination status of yourself, or other attendees, has a huge effect on the risk estimate. If no one is vaccinated, it soars to 630 microCOVIDs. (Did I mention about getting vaccinated? Get vaccinated.)

So I guess I will be going to that barbecue!

Fantastic essay, Steve!

If anyone invites me to a BBQ, I will feel safe(r) in going.